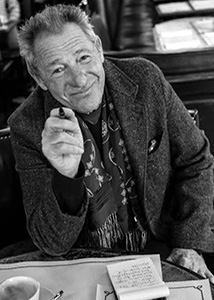

Playwright and screenwriter Israel Horovitz was born in Massachusetts in 1939. His plays include “The Indian Wants the Bronx,” “Park Your Car in Harvard Yard,” “The Primary English Class,” and “Line,” now in its 40th year of continuous performances at the 13th Street Rep. The author of such screenplays as “Author! Author!” and “My Old Lady,” he teaches screenwriting at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

Playwright and screenwriter Israel Horovitz was born in Massachusetts in 1939. His plays include “The Indian Wants the Bronx,” “Park Your Car in Harvard Yard,” “The Primary English Class,” and “Line,” now in its 40th year of continuous performances at the 13th Street Rep. The author of such screenplays as “Author! Author!” and “My Old Lady,” he teaches screenwriting at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

“I would say the arts were not in any way on the radar in our home,” says the writer Israel Horowitz of growing up in Wakefield, Massachusetts. “My mother used to stand at the sink and sing at full voice, but that’s about it. And while she was very gentle and loving, my father was very tough. With my parents in mind, I’ve written some very gentle, loving plays and some very tough plays.”

How did Horovitz—the son of a truck driver turned lawyer—come to be a playwright at all? “I wrote a novel when I was 13 and sent it to Simon & Schuster, not mentioning my age, of course. It was rejected, but it was praised for its ‘childlike quality’,” he says laughing. “That was demoralizing! Having failed as a novelist I tried something else and wrote a play called The Comeback. Nobody said it was a good play but everybody did say it was ‘a play.’ So I thought, ‘I know who I am.’ I never looked back from that.” To this day, Horovitz has written more than 70 produced plays. “I try not to write the same play over and over again,” he says. “I’ve always been eclectic in that sense. I’ve always wanted to keep it fresh.”

Reflecting back on when he was a young playwright in New York, Horovitz remembers it as a good time for writers. “It seemed easier to get produced and my generation of playwrights was really quite successful,” he says. “Think about who was here: Sam Shepard, Lanford Wilson, John Guare, Leonard Melfi, Terrence McNally, Rochelle Owens; a long list of vibrant, young writers who were fairly well known. You’ll have to ask somebody else why it was happening, but I was certainly glad it was. In 1968 I had four of my plays running down town.”

In addition, Horovitz had the benefit of being mentored by established authors. The memory of that gave him the impetus to teach, something he’s grown to love. “There’s a lot of giving back in teaching,” he says. “When I was a young guy starting out I was lucky enough to have authors like Wilder, Ionesco, and Beckett as mentors. I think we have our fathers of ‘choice’ and our fathers of ‘chance.’ My biological father didn’t have a clue about what I was doing. But I met these writers who took an interest in me and guided me.” As a result, Horovitz feels a big responsibility to turn around and do the same. “And the selfish part of it is being in touch with younger writers,” he admits. “They encourage me to rethink how and what I do. It’s kept me writing.”

Horovitz first moved to the City in 1965 and lived on Riverside Drive. After writing the screenplay for The Strawberry Statement, he used that money to buy a house on West 11th Street where he still resides. “When I moved onto the street it was called ‘Writer’s Block’,” he recalls. “There were about twenty writers here. One day Terence McNally knocked on my door—our houses shared a common wall—and introduced himself as a fellow playwright. We became very close friends.”

Horovitz first moved to the City in 1965 and lived on Riverside Drive. After writing the screenplay for The Strawberry Statement, he used that money to buy a house on West 11th Street where he still resides. “When I moved onto the street it was called ‘Writer’s Block’,” he recalls. “There were about twenty writers here. One day Terence McNally knocked on my door—our houses shared a common wall—and introduced himself as a fellow playwright. We became very close friends.”

“Community is like that,” he continues. “You have to want it to have it. We came here back in the day because you felt Greenwich Village was a place where an artist should be. Now it’s all CEOs on this street. It’s definitely not a Bohemian writer’s block anymore.” He laughs. “I could never buy my house today! That’s an enormous change because it was absolutely affordable when I arrived.”

And yet securely ensconced in the West Village, Horovitz admits he couldn’t live anywhere else. “It’s my home town and it really is a village,” he says. “You come back from traveling and it feels like home. I have to admit that I don’t often venture above 14th Street! I have my whole family living here as well. It’s wonderful. I think kids who grew up in the Village never get over it. It seems like that particular beat goes on.”

Photo: Jean-Marie Marion, Paris