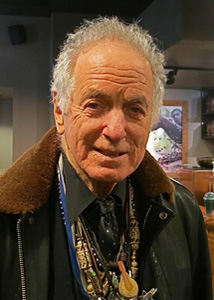

Composer, conductor, and author David Amram was born in Philadelphia in 1930. He’s written over 100 orchestral and chamber music works, as well as Broadway musicals, operas, and scores for such films as “Splendor in the Grass” and “The Manchurian Candidate.” David is the subject of the recent documentary film entitled “David Amram: The First 80 Years.”

Composer, conductor, and author David Amram was born in Philadelphia in 1930. He’s written over 100 orchestral and chamber music works, as well as Broadway musicals, operas, and scores for such films as “Splendor in the Grass” and “The Manchurian Candidate.” David is the subject of the recent documentary film entitled “David Amram: The First 80 Years.”

When David Amram was a boy, his parents decided to work for the war effort. So they moved the family from a 160-acre farm in Pennsylvania to a tiny house in Washington, D.C. “It was what they called a ‘checkerboard’ neighborhood because black and white folks lived together,” he says. “In 1942, D.C. was still officially segregated except for a few areas such as ours. As a result, I was surrounded by all kinds of incredible music: gospel, church, jazz, and the blues. It was all part of the neighborhood experience.” Amram was already studying classical musical but this exposure opened up the world of jazz to him too and he decided to pursue both.

After high school, Amram attended Oberlin College. At that time, school policy forbade anyone to play jazz in the piano room. “When I told the music department that I wanted to play jazz AND write symphonies, they thought I had a mental problem and tried to discourage me,” he says, laughing. “While I appreciated their sincerity, I wanted the option to fail at something before I gave up. And it was good to have that experience because it taught me about what it takes to be an artist. It’s a lifetime pursuit and it takes very hard work.”

Amram’s latest piece, “Greenwich Village Portraits,” is a testament to this fortitude. “I worked tremendously hard on this piece,” he says. “I wanted to use it as a way to honor the people and streets of a fantastic neighborhood in a great city that’s given so many of us a life that we never would have had. That’s what kept me going to finish it. The beautiful thing about a composition is that you’re trying to build something that has value and is meant to last. Not as an ego trip, but as a thank you note for being alive and to all the people who are no longer here.”

Amram moved to the City in 1955 then, two years later, to 114 Christopher Street. “The Village was wonderful then,” he remembers. “A real community. I was constantly meeting these amazing people and having wonderful conversations. I met so many artists of all mediums who had (barely) lived through the Depression. Somehow they had managed to not only find a way to pursue their dreams, but then went out of their way to encourage a young hayseed like myself to dare to pursue mine as well.”

And what about the vast changes to the neighborhood over the years? “People say nowadays that the Village isn’t really the Village anymore,” Amram says. “But when they do I ask them, ‘What would O’Henry say if he came back and saw how Washington Square has changed? Or what would Edna St. Vincent Millay say?’ I guess it’s part of growing old to say, ‘Things just ain’t what they used to be.’ But they never are!”

And what about the vast changes to the neighborhood over the years? “People say nowadays that the Village isn’t really the Village anymore,” Amram says. “But when they do I ask them, ‘What would O’Henry say if he came back and saw how Washington Square has changed? Or what would Edna St. Vincent Millay say?’ I guess it’s part of growing old to say, ‘Things just ain’t what they used to be.’ But they never are!”

Besides, Amram feels that rather than screaming the blues, artists should be the ones passing on that wonderful history. “Right now, it’s ‘full greed ahead’ in the Village,” he says. “But if you preserve its spirit, people will find that it can still exist here. We’re not going to let this legacy die because some people who are culturally and spiritually deprived have suddenly taken charge. It’s our gig to be respectful to them—they have to support their families after all—but at the same time we have to show others there’s an alternative and not assume this is the way it has to be.”

Amram hasn’t lived in the Village since 1994, when his landlord was able to successfully evict him from his rent-controlled apartment. Since then, he’s made his home up in the Putnam Valley. However, this neighborhood still has a hold on him. “When I come back to the Village to play in a club, I think of how lucky I am to have been here in 1955 and to still be here now,” he says. “If I hit the lottery and became a multimillionaire I’d move back to the Village in a minute. That’s because I love it. It’s really one of my homes as long as I’m alive.”

Photo: Maggie Berkvist