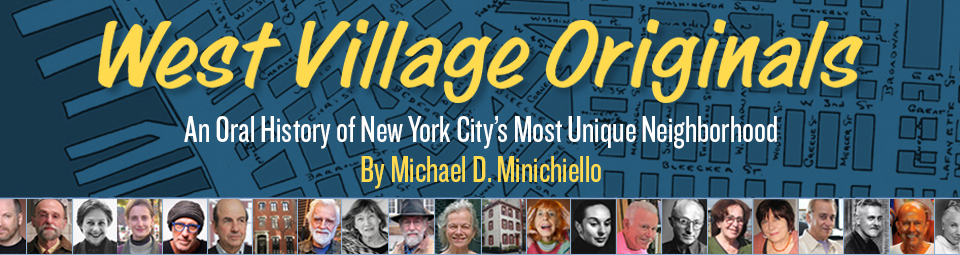

Photographer Suzanne Poli was born in Gowanus, Brooklyn. Poli’s photographs are represented in the collections of numerous institutions and have appeared in film and on television. Her image “Nightsticks” opens the classic black-and-white American Experience PBS documentary “Stonewall Uprising.” Poli has lived on Christopher Street for over fifty years. View her work at www.suzannepoli.com.

Photographer Suzanne Poli was born in Gowanus, Brooklyn. Poli’s photographs are represented in the collections of numerous institutions and have appeared in film and on television. Her image “Nightsticks” opens the classic black-and-white American Experience PBS documentary “Stonewall Uprising.” Poli has lived on Christopher Street for over fifty years. View her work at www.suzannepoli.com.

“I’ve photographed ever since I was little,” says photographer Suzanne Poli. “I took the family pictures for birthdays and holidays. All of the ones we have, in fact. Then I began to paint and I loved it. I was really good at it. But I started to use the camera as a means for recording my daily life. It was very exciting and gradually I stopped painting and began photographing every day.” Suzanne’s parents tried to nudge her along a different path, however. “There was always dialog about how I should be a secretary and this other kind of person, not the one I was,” she says. “So they were surprised when ‘this other person’ found a voice. They knew I was talented but they discouraged me by saying ‘You have stars in your eyes’ or ‘You can’t do that.’ The push and pull of it all was tough.”

The irony is that Poli definitely thinks she got her artistic bent from her parents. “My father was very sweet, gentle, and kind,” she says. “There was a cultured quality about him that I really admired. He was elegant even though the work he did was bad for his health. My mother was very feisty, vivacious, and descriptive. She had a dark side as well from a life that hadn’t been easy. This is where I got a lot of my talent from.”

To support herself, for many years Poli worked as a waitress in a Village restaurant called Kenneret. “I didn’t particularly like it. It was really hard. No wonder I made sure my daughter got an Ivy League education,” she says, laughing. “But through all of that I had my own dark room and studio, which was my passion and kept me alive and connected. I can only thrive if I have a special place. It would have been better if I had gone to school, but I didn’t have the support structure. It would have given me more confidence to take things for myself. But the journey has been worth it. My life was so full and rich anyway.” As for the “artistic moment,” Poli claims the best one is when she’s creating the image. “That moment is a very spiritual place to be. It’s a place that keeps evolving, a very soothing and healing place. It’s often said that my images are very thick with feeling. I work really hard on an image. I’m composing and crafting it as I look through the viewfinder. I like to say that’s a moment when I’m actually focused.”

Since the very first Gay Pride parade fifty years ago, Poli has been photographing it, both from her window and on the street. “I feel when I’m photographing that I’m actually moving a cause forward and creating the change that is happening,” she says. “Christopher Street was always a place for protest and the march started as a protest against ill treatment. In a way, I feel I helped create the movement. I was very involved with gay rights because I thought that everybody should have the right to be who they are. I was also deeply involved with the AIDS movement. But whether the fight is about race, gender, or sexual preference I have to support it because this is who I am. I live for social causes and have very strong political feelings.”

Having lived on Christopher Street for over 50 years, Poli has seen her share of changes. “It was very special and different when I first lived here,” she says. “There were wonderful, individual shops on the street. I suppose all the fancy haute couture shops that eventually moved in made it ‘nice’ in that everything got gentrified and cleaned up. It made the neighborhood more upscale, but I don’t know. It’s still lovely and even today there’s a very thick palette of passion here. The change, though, is pretty drastic. I don’t know where it’s going but I’m sure it will always sustain itself in some way. It will always be a special place. When people come to the West Village they have a different way of treating the neighborhood. They have a certain kind of respect for it and find it very special.”

Having lived on Christopher Street for over 50 years, Poli has seen her share of changes. “It was very special and different when I first lived here,” she says. “There were wonderful, individual shops on the street. I suppose all the fancy haute couture shops that eventually moved in made it ‘nice’ in that everything got gentrified and cleaned up. It made the neighborhood more upscale, but I don’t know. It’s still lovely and even today there’s a very thick palette of passion here. The change, though, is pretty drastic. I don’t know where it’s going but I’m sure it will always sustain itself in some way. It will always be a special place. When people come to the West Village they have a different way of treating the neighborhood. They have a certain kind of respect for it and find it very special.”

Photo: Bruce Poli