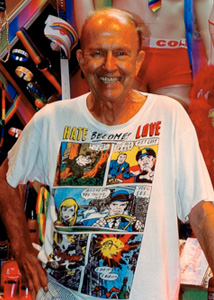

Playwright and author Robert Heide was born and raised in Irvington, New Jersey. The author of numerous plays, Heide has also co-authored many books about collecting memorabilia with his lifetime partner, John Gilman, including three titles for Disney. A West Village resident since 1958, Heide just had a collection of his plays, entitled “Robert Heide: 25 Plays,” published by Michael Smith Fast Press.

Playwright and author Robert Heide was born and raised in Irvington, New Jersey. The author of numerous plays, Heide has also co-authored many books about collecting memorabilia with his lifetime partner, John Gilman, including three titles for Disney. A West Village resident since 1958, Heide just had a collection of his plays, entitled “Robert Heide: 25 Plays,” published by Michael Smith Fast Press.

Growing up with what he describes as a “controlling” father, Robert Heide was able to find his own creative path through, paradoxically, his father’s help. “He was the kind of man who said that movies and reading were a waste of time,” Heide says. “But I actually think he was a thwarted creative type that felt he had to earn a buck instead. I had piano and art lessons growing up. My father paid my college tuition and when I moved into New York he paid my rent for about a year, and even paid for my acting lessons. So even though he had all sorts of personal issues, he wanted something different for me than what he had.”

Heide attended Northwestern University where he studied acting. “I wanted to be Marlon Brando or Jimmy Dean,” he says, laughing. “When I came to New York, I studied with Uta Hagen and Stella Adler, who befriended me. However, one day Judith Malina, co-founder of The Living Theatre, said to me, ‘You’re not an actor. Go home and write a play!’ So, I wrote ‘Hector,’ had it staged at the Cherry Lane, and Jerry Tallmer gave me a rave review.” This began a string of plays with such titles as “West of the Moon,” “The Bed,” which was also filmed by Andy Warhol, “Crisis of Identity,” and “Suburban Tremens,” appearing either Off-Broadway or at venues like Café Cino, LaMama, and Theatre for the New City.

According to Heide, many of his plays have existential and absurdist turns of people being indifferent to others. Where did that come from? “I’m not exactly sure,” he says. “It’s a combination of my life and other people that I know. Edward Albee, who was a friend, once said to me, ‘Characters are living in your head that want to be born in a play. They’re really pushing you to write.’ As for my style, well, I guess I was influenced by Beckett and Pinter. Pinter is always about what’s going on underneath the surface. We were all playing it very cool back then. Nobody expressed a lot of emotions in those days. We saw these Bergman and Antonioni films confronting the emptiness of existence and our work reflected that. It was a different kind of theatre.”

“It was terrific being in New York and the Village back then,” he continues. “Anywhere you went things were happening: at Judson Church, the Night Owl, or Café Cino, where I met Bob Dylan. At the Gaslight Café I heard Jack Kerouac, Alan Ginsberg, and Diane di Prima reading their work. You could feel an energy all over the Village. Unlike the 50’s where it was about being a rebel without a cause, it was the 60’s and we became rebels with a cause. That’s because we wanted a revolution with love.” It was when the shooting at Kent State happened that everything changed. “All hell broke loose in the 70’s,” Heide says. “It became about the excesses of the bars, discos, and places like Studio 54.”

Asked about what he misses from his early days, Heide laughs and responds, “On that I could say practically everything!” However, the passage of time has also afforded him some perspective on life. “Some people like you, some don’t,” he muses. “It’s your human life that’s important; who you are and who your friends are. And I understand that human beings are not perfect. We all have a darker side and feel doubt. I recently reread Kierkegaard who suggests taking a leap into blind faith and to focus on positive life. I think that’s good advice!”

Asked about what he misses from his early days, Heide laughs and responds, “On that I could say practically everything!” However, the passage of time has also afforded him some perspective on life. “Some people like you, some don’t,” he muses. “It’s your human life that’s important; who you are and who your friends are. And I understand that human beings are not perfect. We all have a darker side and feel doubt. I recently reread Kierkegaard who suggests taking a leap into blind faith and to focus on positive life. I think that’s good advice!”

Referring to his recently published collection of plays, Heide worries that he’s campaigning for himself. “But the collection really is a kind of document of the Village in those days,” he says. “I’m not bragging about my plays, it’s just what we were doing. Like Bob Dylan was just writing his songs. When Dylan received the Noble Prize, my partner, John, said the prize wasn’t for him so much as for Greenwich Village itself. And he’s right. That’s the turf and that’s what it was about!”

Photo: George Bonanno