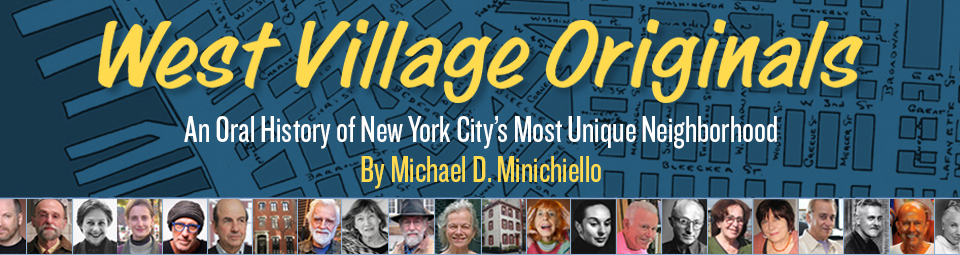

Writer John Tytell’s works on such literary figures as Jack Kerouac, Ezra Pound, Allen Ginsberg, Henry Miller, and William S. Burroughs have made him a leading scholar of the Beat Generation. His latest book is “Reading New York,” a “hybrid memoir” of both growing up and reading in the City. A longtime professor at Queens College where he still teaches literature, Tytell and his wife, Mellon, moved to Perry Street in 1967.

Writer John Tytell’s works on such literary figures as Jack Kerouac, Ezra Pound, Allen Ginsberg, Henry Miller, and William S. Burroughs have made him a leading scholar of the Beat Generation. His latest book is “Reading New York,” a “hybrid memoir” of both growing up and reading in the City. A longtime professor at Queens College where he still teaches literature, Tytell and his wife, Mellon, moved to Perry Street in 1967.

Born into a family of diamond merchants in Antwerp, Belgium in 1939, John Tytell emigrated to America with them two years later and grew up on the Upper West Side. Afflicted with vernal catarrh until the age of 12, Tytell was warned that—because of sensitivity to light—reading would only strain his already compromised eyes. “As a kind of compensation I began reading by flashlight at night when no one knew,” he recalls. “That experience of reading Melville and Poe, among others, gave me a sense of a great American literary tradition. That was one of the things that led me on the path that I later took.”

That path was going to college to study history, philosophy, and—ultimately—literature, which was his real passion. The path also included eschewing the family diamond business. “I guess I was the first member of my family not to go into my father’s business, which was more or less obligatory,” he says. “But I thought that since I was in America, I was going to go my own way.”

Tytell’s interest in the Beat Generation began while in graduate school and he edited an anthology for Harper & Row called The American Experience: A Radical Reader. “The book was one of the first attempts to understand the turbulence of that era and its publication caused some notoriety”, Tytell says. His interest was further piqued by the torrent of negative reception the Beats received during the 60’s. “The establishment critics had positioned the Beats as the new barbarians at the gates,” he says. “Kerouac was called the “Latrine Laureate” by Time. When his masterpiece, Visions of Cody, was posthumously published in 1973, I was asked to review it for Partisan Review. I was knocked out by the book; just overwhelmed by the sheer rhapsody of its rhythmic power. So that became a motive for me: to tell what I had discovered to a larger public. That’s what any literary or social critic should want to do.”

When Tytell was hired by Queens College in the sixties, it was rather as a specialist on Henry James, the subject of his graduate dissertation. “When I first proposed that I wanted to teach a course on the Beats, they said, ‘No way, you teach Henry James.’ So I taught the first course on the Beats in America at the New School instead, then at Rutgers, and then Queens finally decided to let me start doing it there. Every time I taught that course it was major enrollment. It made my colleagues who were teaching Victorian literature feel a little inadequate! I’m still teaching the course.”

An ad in the Village Voice in 1967 led Tytell and his wife to their apartment on Perry Street. “I thought the West Village was the most beautiful part of Manhattan. I grew up on Riverside Drive where the buildings make you feel claustrophobic so I loved the architecture and the light here. Plus, it had a music scene and a bar scene that you couldn’t find anywhere else. That represented a kind of freedom for me. It was the only part of the city I could see myself living in.”

“When we moved here it was much more working class in our building,” he remembers. “They were all ordinary people working ordinary jobs. One family were even longshoremen. The docks were still active in those days and a lot of people in the neighborhood worked on them. And the neighborhood shops were all Mom and Pop grocery stores. Of course, things have changed drastically since then.” He pauses to consider for a moment and then laughs. “But everything changes all the time and smart people go with the flow!”

“When we moved here it was much more working class in our building,” he remembers. “They were all ordinary people working ordinary jobs. One family were even longshoremen. The docks were still active in those days and a lot of people in the neighborhood worked on them. And the neighborhood shops were all Mom and Pop grocery stores. Of course, things have changed drastically since then.” He pauses to consider for a moment and then laughs. “But everything changes all the time and smart people go with the flow!”

Summing up a life spent in the West Village, Tytell puts it all in perspective. “I’ve been delighted and privileged to be here”, he says. “Both my wife and I have never wanted to leave. We’ve lived all over the world, but we’re always so happy to come back here. In the final analysis, I think what the Village always represented to me was a sense of possibility, and that’s still here.”

Photo: Mellon Tytell