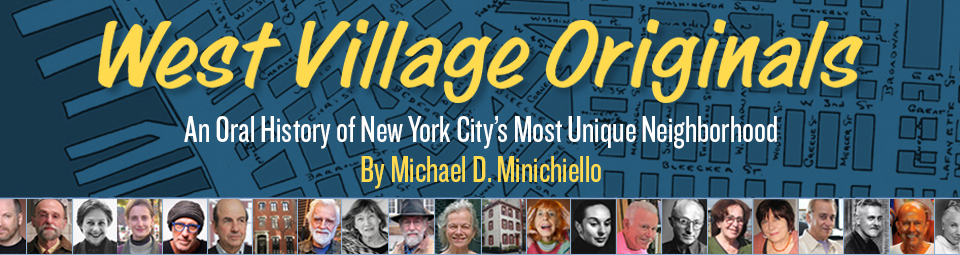

David Gruber enjoys a lengthy resume of membership in community organizations, including president of the Carmine Street Block Association, president of the South Village Landmark Association, and chairman of the Arts and Institutions Committee for Community Board 2. He has lived with his wife Helen, a graphic designer, on Carmine Street for thirty years.

David Gruber enjoys a lengthy resume of membership in community organizations, including president of the Carmine Street Block Association, president of the South Village Landmark Association, and chairman of the Arts and Institutions Committee for Community Board 2. He has lived with his wife Helen, a graphic designer, on Carmine Street for thirty years.

For Manhattan-born David Gruber, it took a noisy restaurant to get him started in community service. “I had spent my life not really being involved,” he admits. “We had lived on Carmine Street for years when this restaurant opened and installed loudspeakers that went into the back courtyard, which was residential. We complained about it and we were ignored. So I organized the Carmine Street Courtyard Organization, which included the seven families living there. We went to he community board and protested the restaurant’s application for a sidewalk license.”

The community board ruled in the residents’ favor. However, the restaurant then approached another City agency, which did, in fact, grant them a license. This made Gruber really angry. “I then went to the full board meeting,” he recalls. “I asked them just what the point was of the board turning down the restaurant’s request, only to be ignored by another agency? At that time, Audrey Leeds was the chair of the sidewalk committee and said, ‘So come and join the committee as a public member.’ And I did.”

Gruber continues. “At the time, maybe 10, 12 years ago, the city’s agencies did what they wanted. We repeatedly turned down liquor licenses and they routinely overturned our decisions. But I got to learn the system and, given my background with the planning commission, I became a member of the zoning committee. Over time, Community Board 2 became very focused. And now, community boards in general have become very empowered in this city. You have people on the boards that really know their stuff. Politicians listen. Council members listen. The planning commission listens. We resonate much more with the city agencies.”

How has the Village changed since he first moved in? “It’s become much more of an area for nightlife,” Gruber observes. “People come to the Village and think they can raise hell because there’s no community. That isn’t true, but the presence of lots of bars and certain stores—such as the porn shops and tattoo parlors on lower Sixth Avenue—doesn’t help.” He does offer a note of conciliation. “The Community Board is not really against anything, we’re just against excess,” Gruber explains. “That’s what people don’t realize: how citizens like myself and hundreds of others are preserving this neighborhood for the generations that come after us. Hopefully they’ll know about the work we put in and will say, ‘How nice that our predecessors battled so that we can still see the sky.’ That, however, will be an interview for the next generation!”

How has the Village changed since he first moved in? “It’s become much more of an area for nightlife,” Gruber observes. “People come to the Village and think they can raise hell because there’s no community. That isn’t true, but the presence of lots of bars and certain stores—such as the porn shops and tattoo parlors on lower Sixth Avenue—doesn’t help.” He does offer a note of conciliation. “The Community Board is not really against anything, we’re just against excess,” Gruber explains. “That’s what people don’t realize: how citizens like myself and hundreds of others are preserving this neighborhood for the generations that come after us. Hopefully they’ll know about the work we put in and will say, ‘How nice that our predecessors battled so that we can still see the sky.’ That, however, will be an interview for the next generation!”

One thing Gruber is proudest of is his effort to rehabilitate Father Demo Square at Sixth Avenue and Carmine Street. “That’s almost my legacy,” he says. “Back in 2000, the park was filthy. It was open all night, there were screaming fights, and homeless people were living in it, draping their blankets over the benches or sleeping in cardboard boxes. It was a very hostile environment and it no longer functioned as a neighborhood park.” So Gruber formed the Friends of Father Demo to lobby for change. It was a long fight, but they prevailed. “Now it’s a peaceful park that closes at midnight,” he says with pride. “I think it’s the jewel in the crown of New York parks. Per square foot we’re one of the most highly used parks in the city. It’s working, and the community—senior citizens, kids, tourists—is actually using it.”

With regards to what he feels is the biggest challenge facing the Village today, Gruber takes the developers to task. “They come into the far West Village with its beautiful old buildings and water views and say, ‘We love it here. Let’s see how we can kill it!’” He laughs. “We’re under siege because we have this beautiful community that’s different from any other neighborhood in Manhattan and developers come in and put up buildings totally out of scale. So the test is to keep this an historic part of New York. Our mandate here is not to say there can’t be change, but that it needs to be respectful of the history and scale of the West Village. That’s the challenge for me—and all of us—moving forward.”

Photo: David Gruber