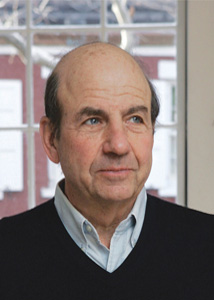

Journalist, humorist, and novelist Calvin Trillin was born in Kansas City in 1935. After a stint in the U.S. army, Trilin worked as a reporter for Time Magazine before joining the staff of The New Yorker in 1963. He was also a regular contributor to The Nation, as well as being a renowned writer on cuisine. He moved to New York City in 1961 and has been a resident of the West Village since 1969.

Journalist, humorist, and novelist Calvin Trillin was born in Kansas City in 1935. After a stint in the U.S. army, Trilin worked as a reporter for Time Magazine before joining the staff of The New Yorker in 1963. He was also a regular contributor to The Nation, as well as being a renowned writer on cuisine. He moved to New York City in 1961 and has been a resident of the West Village since 1969.

When writer Calvin Trillin moved to Grove Street in 1969, partitioning Greenwich Village into even smaller areas was not common. “I’ve never known to this day where the ‘West Village’ is,” he admits. “When I moved here I’m not sure the phrase was used very much. I might be wrong about that, but if it had been used I would’ve thought it meant west of Hudson. I always thought I lived in Greenwich Village and didn’t know I lived in the West Village.”

Growing up in Kansas City, Trillin made it east when he attended Yale University, eventually becoming a writer and chairman of the Yale Daily News. A career as an author was quite a departure from the family business. In fact, his father was a grocer. “He started with a little store,” he recalls. “He didn’t go to college himself, but he decided he wanted his son to go to Yale. I never knew how he paid for my college tuition until after he died. It happened that in his first store there was a bread company that gave you a 2% rebate if you displayed their bread and paid your bill on time. It was that rebate money—which he put away for years—that paid for my tuition at Yale.” After graduating, Trillin did a stint in the army, worked in the Atlanta bureau of Time Magazine, and then settled permanently in New York when Time transferred him here.

When Trillin and is wife, Alice, moved to the West Village, it was with the idea of trying something new. “A that time,” he recounts, “the custom of converting the commercial and industrial structures west of Hudson Street into residential buildings hadn’t really started. It just wasn’t a common thing then. My wife and I looked at a sort of stable on Washington Street with the idea of turning it into a house. That, however, was a truly cockamamie scheme and luckily we didn’t do it!” They eventually settled in a town house on Grove Street. “Back then, the Village looked about the same as it does now,” Trillin says. “Since this part of the Village is a historic district, changing facades is difficult. As a result, there are still a lot of people making movies here because you can get the 1890’s or the 1930s look very easily.”

Recalling the Village of those days, Trillin says, “It was obviously a little funkier then.” But it was also easier to do certain things. “I remember when my girls and I first ran into the Halloween Parade,” he says. “We didn’t even know about it. They just passed us on the street and there were a couple of hundred people in great costumes. There was also a small police presence so we could get in and out of the parade at will. I think it’s difficult now to have that kind of neighborhood event. With hyper-communication and a lot of people able to move around quickly, it’s almost impossible to have a little community event that doesn’t become either too large or get crushed.” On the other hand, there are some things that have greatly improved the quality of life in the neighborhood. “When I first moved here we didn’t have, of course, the park along the Hudson. Now it’s a wonderful water park and my grandchildren adore it.”

Recalling the Village of those days, Trillin says, “It was obviously a little funkier then.” But it was also easier to do certain things. “I remember when my girls and I first ran into the Halloween Parade,” he says. “We didn’t even know about it. They just passed us on the street and there were a couple of hundred people in great costumes. There was also a small police presence so we could get in and out of the parade at will. I think it’s difficult now to have that kind of neighborhood event. With hyper-communication and a lot of people able to move around quickly, it’s almost impossible to have a little community event that doesn’t become either too large or get crushed.” On the other hand, there are some things that have greatly improved the quality of life in the neighborhood. “When I first moved here we didn’t have, of course, the park along the Hudson. Now it’s a wonderful water park and my grandchildren adore it.”

On the subject of neighborhood as destiny, Trillin lays his success firmly at the feet of the Village. “I always thought I couldn’t really have made it uptown,” he says, laughing. “I think the Village is full of people like me who are from the rest of the country. In a way, it’s more like where we came from than the rest of Manhattan because it’s mostly low-rise. You can actually see the sun and you’re likely to have a next-door neighbor instead of someone you just see in the elevator. It’s less formal as well. I once talked to a historian at NYU who said that was true even of the early Village bohemians; many of them were from small towns. They felt more comfortable in the Village. For people who come from the rest of the country, it just seems like a more natural place.”

Photo: Richard Drew