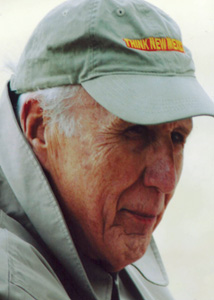

Born in 1923 and a lifelong New Yorker, attorney Whitney North Seymour served in the New York State senate from 1966–68. He was also U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York from 1970–73 when he represented the government in its fight to prevent the New York Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers.

Born in 1923 and a lifelong New Yorker, attorney Whitney North Seymour served in the New York State senate from 1966–68. He was also U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York from 1970–73 when he represented the government in its fight to prevent the New York Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers.

“For me, the West Village has always been characterized by action and involvement,” says Whitney North Seymour, Jr. “And three kinds of action at that: individual, community, and political.” A resident of West 11th Street since he and his wife, Catryna, moved there as newlyweds in 1951, North has spent most of the ensuing years practicing what he preaches. For him, activism is not only a calling, but also a way to give back to what he considers a very special part of this city. “If we’re going to enjoy the West Village, it’s our obligation to pay it back for that privilege. You do that by giving time to local organizations and fighting against people who would exploit and ruin it.”

On an individual level, Seymour’s activism has run the gamut from writing books and newspaper articles, to being president of the Park Association of New York City and the Municipal Art Society, to taking on small challenges with big payoffs. One story in particular illustrates his style. “After a trip to Paris and seeing how sidewalk cafes added such life to that city,” he recounts, “Catryna and I returned to New York and realized there were virtually no sidewalk cafes here. So we drove up and down the streets of the Village, writing down the addresses of bars and restaurants that were likely sites for sidewalk cafes. Then we mailed memos to the owners suggesting they put out cafes and that it would only cost—in those days—$25 for the license. Next spring there were dozens of sidewalk cafes around the village! This is an example of how individuals can make a difference.”

The second type of action comes from the community, as Seymour explains it. There are block associations in every segment of the West Village as well as community organizations, such as the one on Charles Street that gave birth to WestView. “They come and go as people live there and move on,” he says. “But it’s part of the quality of our community that I think sets it especially apart, including some of the bigger groups like the Greenwich Village Society for Historical Preservation. That’s a very good example of a current organization that has a lot of different people attending rallies and such. Within my time, Jane Jacobs was very active and vocal in espousing the notion of what makes cities great in terms of participation and scale. She was involved in the movement—as I was back in the 50s—to get traffic out of Washington Square.”

The second type of action comes from the community, as Seymour explains it. There are block associations in every segment of the West Village as well as community organizations, such as the one on Charles Street that gave birth to WestView. “They come and go as people live there and move on,” he says. “But it’s part of the quality of our community that I think sets it especially apart, including some of the bigger groups like the Greenwich Village Society for Historical Preservation. That’s a very good example of a current organization that has a lot of different people attending rallies and such. Within my time, Jane Jacobs was very active and vocal in espousing the notion of what makes cities great in terms of participation and scale. She was involved in the movement—as I was back in the 50s—to get traffic out of Washington Square.”

As for political action, it was by running for elected offices that Seymour learned some valuable lessons about politics. “The village was a wonderful hotbed of political reform in the 1950s and 60s. I first got involved in politics back then. I was Assistant DA and was urged by others to get involved in the political process on the proposition that everyone complains about politics but no one does anything about it.” Amazingly enough, all three of his appointed positions came after he ran for public office and was defeated. “That was because I had shown my willingness to fight,” he remembers. “As a result, I came to the attention of people who made those appointments.”

For Seymour, the overriding benefit of being a politician was what it teaches you about human relations. “Working in politics teaches you respect for different people,” he says. “In politics, people of all different sizes, shapes, and attitudes work together for a common cause. You learn that even though others don’t have the same background as you, good people still try to do what they believe is the right thing. That’s an experience that shapes you for life. I believe the highest responsibility for a human being is to show respect for other people. And I mean on the ground; showing kindness to those who need a helping hand or are lost. The political process is part of what makes you learn how to do that.”

When asked what’s the biggest change he’s seen in the West Village, he quickly responds, “Gentrification. It’s not as scruffy as it used to be. Not scruffy in a derogatory sense but in the sense that people were more natural. You saw and felt the bubbling excitement of people who were doing creative work, having meetings, protesting wrong policies of the government, fighting Robert Moses, or saving the Jefferson Market courthouse. You don’t see much of that anymore. And of course the worse thing has been the arrival of the chauffeured limousines! The Village is so desirable now that people with money and no values have moved in and they’ve become parasites. They take from the Village and they don’t give to it. That saddens me the most.”

It’s not all bad, however. According to Seymour, the things he loves about the neighborhood can still be found here. “The undercurrent is still there,” he admits. “You still find people who want to support creative ideas. You see young people hoping to write their first novel or their first play or paint their first masterpiece. You see people sketching on the street corner. And last night on our block there was a fellow sitting on a chair and playing a cello. It was wonderful.”

For Seymour, a lifetime of activism on behalf of the West Village has provided opportunities to make a difference as well as inspire others to follow suit. “I don’t believe in personal publicity,” he says. “What I do believe in is using your own experience to excite others to go and enjoy similar experiences. That’s always been my real goal in life.”

Photo: Catryna Seymour